Finance & economicsButtonwood

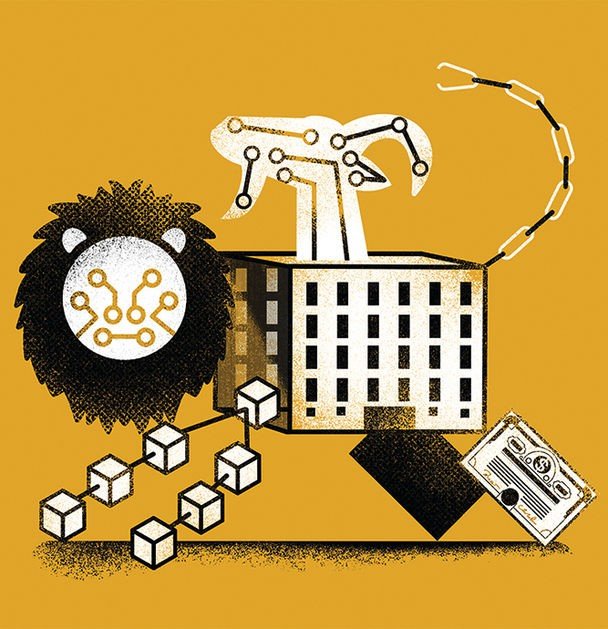

Are financial crossbreeds monstrosities or labradoodles?

Crypto-SPAC fusions shed light on the question

THE ANCIENTS knew the source of real terror. Lions, snakes and goats (apparently) are scary creatures to stumble across, but it is the combination of different bits of them that is the stuff of nightmares. The Chimera, with the head of a lion, the body of a goat and the tail of a snake, whose “breath came out in terrible blasts of burning flame”, was a truly fearsome beast. Yet crossbreeds can also be cute and cuddly. Just think of labradoodles.

What about financial crossbreeds? Are they minotaurs or maltipoos? Finance has adapted and innovated at a frenetic pace over the past few years. In 2019 there were hardly any deals using special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), blank-cheque vehicles which take firms public via a merger. In 2021 they raised $163bn of capital and agreed to take 267 firms public.

As recently as 2020 few people had heard of non-fungible tokens (NFTs), the cryptocurrency chits attached to pieces of digital media, such as a picture or video. But interest rocketed after Beeple, a digital artist, sold one for $69m at auction at Christie’s almost a year ago. Cryptocurrencies and associated trading platforms entered the mainstream. Institutional investors now chatter about including bitcoin in their portfolios. Coinbase, a cryptocurrency trading platform, went public in April 2021. It has a market capitalisation of $45bn.

As these newfangled technologies and financial vehicles have grown in size and scope they have begun to mate. First, in July 2021, Circle, a Boston-based company which issues USDC tokens, a type of stablecoin pegged to the dollar, agreed to merge with Concord Acquisition, a SPAC founded by Bob Diamond, a one-time boss of Barclays, a bank, in a transaction that valued Circle at $4.5bn. Then in December 2021 Aries Acquisition, another SPAC, announced plans to merge with InfiniteWorld, a Miami-based NFT and metaverse-infrastructure platform valued at around $700m.

Keeping up? There’s more. Not to be outdone, on February 11th Binance, a crypto currency trading platform founded in China, announced it was making a $200m investment in Forbes, a publisher and ranker of billionaires, ahead of Forbes going public via a merger with the modestly named Magnum Opus, another SPAC. Binance’s rationale for backing the union, its boss helpfully explained, was that media is “an essential element” as cryptocurrencies, blockchain technology and “Web3”, the supposed next generation of media and internet businesses where crypto-holders run social-media platforms, come of age.

What should an investor make of all this? It is tempting to dismiss these new beasts—call them Cryp SPACtaurs—as nonsense. There is nothing particularly cute or cuddly about the way SPACs typically treat their investors. In part thanks to the fat slice of shares grabbed by deal sponsors, investments in pre-merger SPACs have underperformed major stock indices by around 30 percentage points on average. Add in the risks typically associated with crypto-ventures and some punters may conclude that it looks more appealing to invest with the next Bernie Madoff.

That may also explain why these crossbreeds are yet to reach maturity. Infinite World has not yet completed its merger with Aries. Circle and Concord have not tied the knot either, despite announcing their coupling around eight months ago. The Binance investment in Forbes, meanwhile, seems at least in part motivated by the prospect of the Forbes SPAC deal otherwise failing to come off. The $200m infusion replaced those mulled by other outside investors, who appear to have got cold feet. Perhaps the Chimera and the Cryp SPACtaur are alike: not because they are both monsters, but because they are both seemingly mythical creatures.

Still, the prospect of facing the bright lights of public equity markets might be just what is needed to sort the puppies from the pigs. When quizzed about why the Circle SPAC transaction was taking longer than some others, Jeremy Allaire, Circle’s chief executive, explained that to enter public markets “companies have to be in a position where they have to meet necessary regulatory, disclosure and accounting standards so that the public can invest. That is a good process.” But it can take longer still for firms like Circle, which are “a very new kind of financial institution”. Only when one of them actually goes public will it start to become clear whether Cryp SPACtaurs are beasts to fear or pooches to pet.

For more expert analysis of the biggest stories in economics, business and markets, sign up to Money Talks, our weekly newsletter.