Finance & economicsForward in fear

The reasons behind the current stockmarket turmoil

From Fed tightening to rising wage costs, investors see gloomy prospects ahead

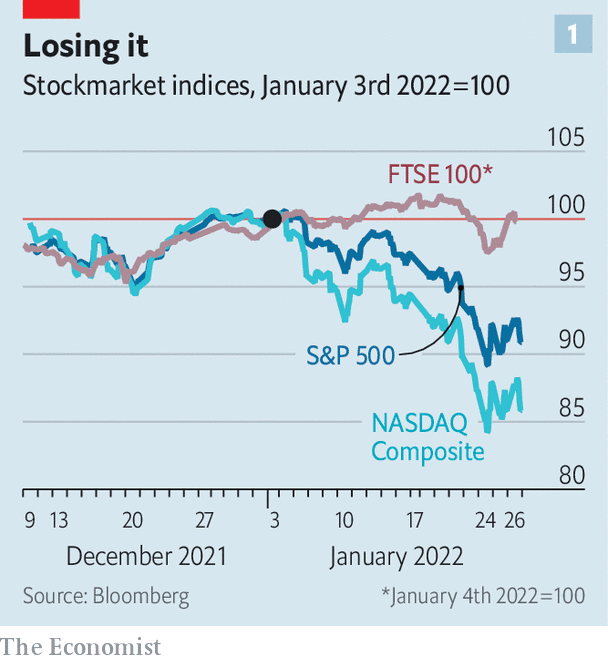

AS STOCK-TRADING screens turned red again on January 25th, one trader was heard to quip that at least some things are falling in price. The day’s fall in share prices took the cumulative loss on the S&P 500 index towards 10% for this year already, only three weeks in. The year-to-date decline in the NASDAQ composite, a tech-heavy index, is well into the double digits. It has been a rotten start to 2022 for stock investors. And the day-to-day numbers for the broad indices do not even do full justice to the turmoil in the markets.

Much of the drama has taken place beneath the surface, at the stock or sector level. Technology shares in particular have fared badly. The FTSE 100 index of British stocks, which is light on technology and heavy on oil and commodity firms, has been more resilient than American indices (see chart). Prices have swung wildly during the trading day. Late last week New York’s markets opened to modest rises in the main indices, only for prices to tumble as the days ended. At the start of this week, the intraday lurches became wider. On Monday, for instance, New York’s trading day began with a big sell-off, which then intensified. At one point the NASDAQ composite was down by almost 5%. Then stocks suddenly rallied. The NASDAQ finished the day up by 0.6%. The S&P 500 index posted a gain of 0.3%, despite being down by 4% at its lowest ebb. Few were fooled by the late rally. Almost everybody, it seems, was braced for more red screens the next day. They duly arrived.

Behind all this action is a market that is always somewhat forward-looking. And what has the market now to look forward to? Quite a lot of trouble, it would seem. In six months’ time, the Federal Reserve will probably have raised interest rates twice, with more to come. The easy money that has supported stock prices will be firmly on the way out. Corporate profits will be squeezed at two ends—from decelerating revenue growth (in a slowing economy) and from rising wage costs. There are, in short, more reasons to be alarmed than to be hopeful. No wonder markets are so jumpy.

Start with a factor that is never far from investors’ thoughts: the Fed. After spending much of 2021 playing down any immediate need for tighter money, the Fed has changed its tune quite abruptly. It sounded a more hawkish note at its monetary-policy meeting in December. The minutes of that meeting, which were published on January 5th, made clear to investors that rates would soon be going up. The reasons for the volte face are obvious enough. Inflation is uncomfortably high. It can no longer be dismissed as transitory. And the labour market is fast running out of spare capacity.

In response to that change in tone, markets have quickly priced in more rapid policy tightening. The rise in long-term real interest rates has been notably sharp. Yields on ten-year Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS), which were around -1% at the start of the year, are now -0.6%. Stockmarkets have had to adjust to this. Higher long-term rates reduce the present value of future corporate cashflows, making shares less valuable. The effect is especially marked for the shares of tech companies, which are priced for profit growth long into the future. Hence the violence of the NASDAQ’s decline.

The Fed is not the only concern. Much of the run-up in markets last year was predicated on a stronger economy and handsome revenues and profits. Extraordinary growth in America was fuelled by low interest rates, pent-up demand and a bumper $1.9trn fiscal-stimulus package. Such impulses are fading. Economists at JPMorgan Chase, a bank, forecast that GDP growth in America will fall from 5.7% in 2021 to 3.7% this year and 2.5% in 2023. There are already some signs that a slowdown is under way. Activity in America’s service industries has fallen to an 18-month low, according to the latest survey of purchasing managers. Retail sales slumped in December. Consumer confidence is low. Some of this can be put down to the Omicron wave. But it may also reflect an ebbing in underlying demand.

As investors consider the demand outlook for the coming months, there is a lot less to excite them. Profits will be squeezed by a slowing economy, and thus slowing revenue, but also by rising costs. Higher oil and commodity prices add to raw-material costs. A bigger headache is labour. The tight jobs market is bidding up the salaries of increasingly scarce workers. “There is real wage inflation everywhere,” lamented David Solomon, boss of Goldman Sachs, on a call to investors last week. His bank had just reported a blowout year for profits, but the nerves of investors were jangled by the one-third increase in Goldman’s wage bill last year. Other businesses that also rely more on brainpower than physical capital will feel the pinch, providing yet another reason why tech shares, especially those of fledgling firms, have come under such selling pressure.

A third big concern is valuation. Stocks in America look terrifyingly expensive. A measure popularised by Robert Shiller of Yale University puts America’s stock prices at a steep 36 times their earnings, adjusted for the business cycle. That is above the reading before the 1929 stockmarket crash (though still lower than the valuation reached at the peak of the dotcom boom of the late 1990s). A reckoning was due, especially for expensive-looking, unproven businesses. ARK Innovation, an exchange-traded fund that invests in young tech firms, has become the shorthand for the more speculative end of the market. It is down by 55% from its peak. There is also greater scepticism about the more established—or at least more familiar—names, such as Netflix and Zoom, which did well from the stay-at-home economy, but have suffered recently. “In short”, notes Michael Wilson of Morgan Stanley, a bank, “the froth is coming out of an equity market that simply got too extended on valuation.”

A concern is that the current selling will feed on itself and cause a rout. Is there anything that might improve the market mood? There are some bits of good news that investors might eventually cling to. Omicron may prove to be the last wave of the pandemic. As it fades, so might the labour bottlenecks behind some of the recent inflation. Reopening can happen in earnest. There are tentative signs that China’s economy is bottoming out. Many emerging markets have already been through a painful adjustment. The EU’s “Next Generation” fund, which will disburse €750bn ($880bn) to member states, still has a lot of fiscal fuel in the tank. A lot of the better news comes from outside America, though. It may not do much for the NASDAQ. And it is hard to feel bullish about Europe with Russian troops amassed on Ukraine’s border.

For now, though, the focus is firmly on the Fed, which concludes its rate-setting meeting on January 26th. Investors nursing hefty losses might hope for a less hawkish tone from Jerome Powell, the central bank’s chairman, and colleagues. Is that likely? The Fed would have reason to worry if the corporate-bond market had come badly unstuck, because it is a vital conduit for funding. But corporate-bond spreads have been fairly stable. Falling stock prices by themselves are—or should be—less of a concern to policymakers. Indeed a market correction might even suit the Fed’s purposes, if it brings the people who have retired early on their stockmarket gains back into work. Or perhaps Mr Powell will blink. We won’t have to wait long to find out.

For more expert analysis of the biggest stories in economics, business and markets, sign up to Money Talks, our weekly newsletter.

The Economist today

Handpicked stories, in your inbox

A daily newsletter with the best of our journalism

Sign up